Every Time America Tried to Buy, Acquire or Take Over Greenland

The town of Ittoqqortoormiit, population 345, in Northeast Greenland, with rare rainbow. Prosaic considering the subject matter.

Welcome to The Great Expedition Company Blog!

In the Great Expedition Blog, we cover and discuss all manner of topics, issues and things to think about when it comes to Greenland, Iceland and the polar regions (Arctic and the Antarctic). We do hope you can benefit from our expedition and travel experience in these areas and use the information found here to make choices about your future travel plans that suit you perfectly. The information contained herein expresses no political or ideological opinions of any kind. This blog post is presented expressly for informational and historical purposes only. and to perhaps partially counter the idea that we should be surprised that this is happening at all since there is a clear history of attempts to buy Greenland.

Quick summary of all the times America tried to Buy Greenland

Although Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat) is today an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, the island has repeatedly drawn the attention of the United States, which has tried to buy, acquire or take over Greenland many times in the last 157 years or so. From the 19th century through the Cold War and into the 21st century, American leaders have viewed Greenland as a strategically valuable Arctic outpost. While the U.S. never succeeded in acquiring Greenland, it has made multiple serious attempts or proposals yo buy Greenland or acquire Greenland.

Here is a brief chronology of the incidents in which the United States has tried too buy, acquire or take control of Greenland, just to set the record straight and be clear about things.

1867–1868 — Post–Alaska Expansion Planning

1891–1909 — The Peary Land Controversy

1916–1917 — U.S. Recognition of Danish Sovereignty over Greenland

1941–1945 — World War II Military Control

1946 - Truman Purchase offer

1951 Greenland Defence Treaty

1951 - 1990s - Cold War Strategic Dominance

2019 - The Trump Proposal Round 1

2025/2026 - Trump Proposal renewed - International community takes heed.

William H. Seward: Intellectual Origins of U.S. Interest in Greenland

William H. Seward played a foundational role in shaping early American interest in both Greenland and the Danish West Indies, even though he was no longer in office when later negotiations unfolded. Seward served as U.S. Secretary of State first under Abraham Lincoln and then under President Andrew Johnson. During this period, he was the most influential advocate of American territorial expansion beyond the continental United States, believing that national power depended on control of strategic ports, trade routes, and emerging global chokepoints.

William H Seward

Seward’s most famous achievement was the 1867 purchase of Alaska from Russia, a deal completed during Andrew Johnson’s presidency. This acquisition reflected Seward’s broader strategic vision: he saw the Arctic and the Pacific not as remote frontiers, but as future centers of commerce and military significance. Within this same worldview, Seward expressed interest in additional Arctic territories, including Greenland and Iceland, and supported internal government studies examining whether Greenland might one day be bought from Denmark. While no formal offer was made during his tenure, Seward’s thinking placed Greenland on the strategic map in Washington for the first time.

US Interests in Greenland & The Danish West Indies: A Quid Pro Quo (1860s–1900s)

Long before the United States formally accepted Danish sovereignty over Greenland, it had already begun pressuring Denmark elsewhere, namely particularly in the Caribbean. American interest in the Danish West Indies dates back to the mid-19th century, when U.S. leaders became increasingly focused on securing strategic naval positions in the Caribbean Sea. This interest intensified after the Civil War, as the United States reasserted itself as a hemispheric power and sought to limit European influence near its maritime trade routes.

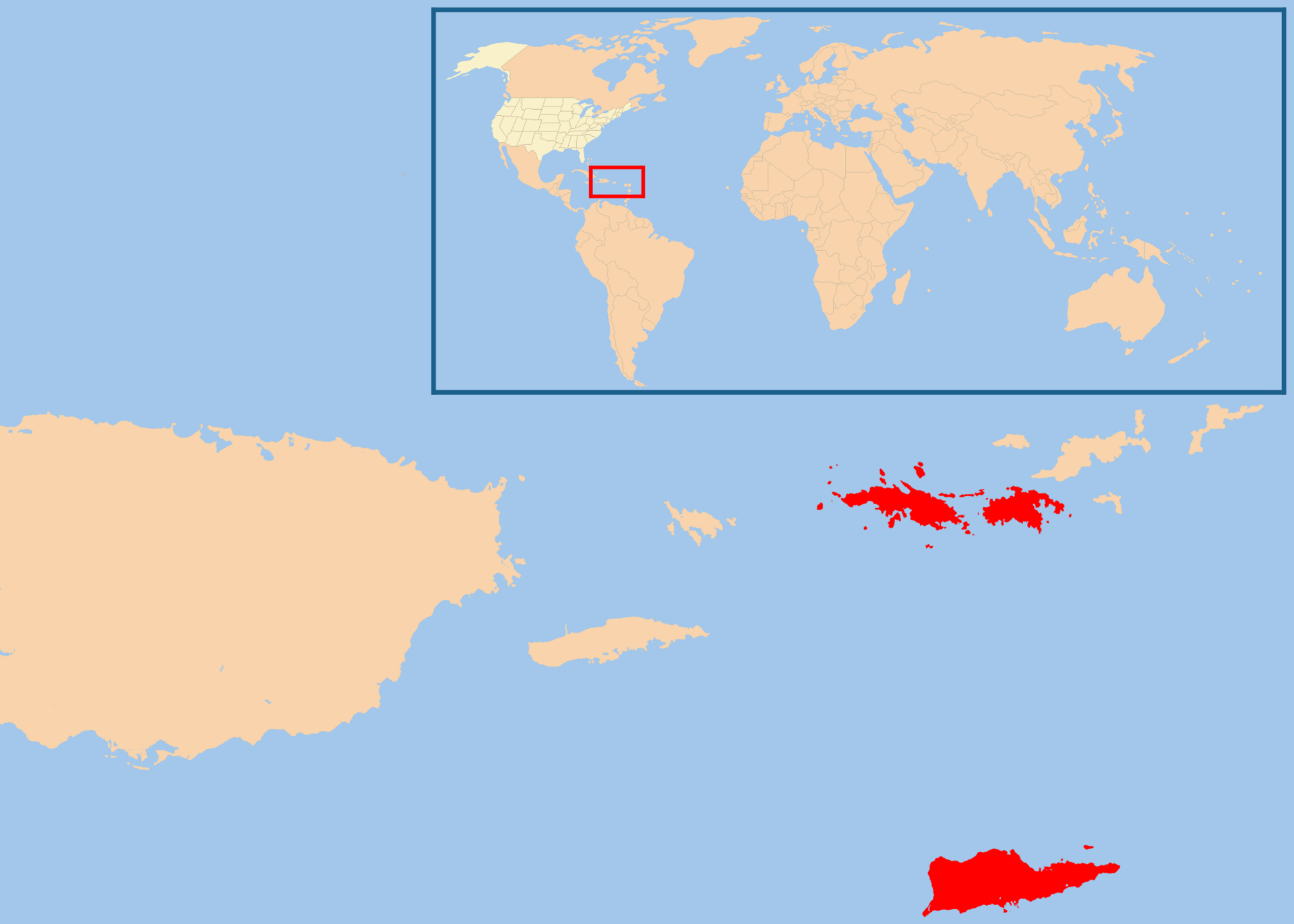

Location of Danish West Indies

In 1867 the United States came closer than ever to acquiring the Danish West Indies, specifically the islands of St. Thomas and St. John. Denmark agreed in principle to sell the territory for $7.5 million, and a local plebiscite held on the islands approved the transfer by a wide margin. Despite this, the deal ultimately failed when the U.S. Senate declined to ratify the treaty before it expired. Domestic political turmoil during Reconstruction, combined with lingering skepticism about overseas expansion, stalled what might otherwise have been America’s first major Caribbean acquisition. In 1889, rumors circulated that Denmark might instead sell the islands to Germany, triggering renewed concern in Washington about a rival European power gaining a foothold in the Caribbean. Negotiations resumed intermittently, and in 1902 the United States and Denmark again drafted agreements, but the deal collapsed in Copenhagen this time.

These repeated failures underscore an important strategic reality: for decades, the United States viewed the Danish West Indies as far more immediately valuable than Greenland. By the early 20th century, this southern focus would directly shape U.S. policy toward Denmark, setting the stage for a pivotal diplomatic trade-off in which Washington prioritized Caribbean security while formally conceding Danish control over Greenland. The United States eventually purchased the Danish West Indies for $25 million in gold.

The United States Accepts Danish Control of Greenland (1916–1917)

The completion of the Panama Canal in 1914 was the moment when the United States formally abandoned any objection to Danish control of Greenland. Greenland had become become strategically secondary to the Caribbean and the canal.

The resulting agreement reflected a pragmatic trade-off. The United States buy the Danish West Indies (renamed the U.S. Virgin Islands), securing the Panama Canal’s Atlantic approaches, while Denmark received unambiguous international backing for its control over all of Greenland.

From Washington’s perspective, this was a rational exchange: Arctic territory held theoretical future value, but Caribbean islands posed an immediate strategic risk. This decision effectively closed the door on any U.S. challenge to Danish sovereignty in Greenland for the next several decades, even as American strategic interest in the island would later re-emerge under very different global conditions during World War II and the Cold War.

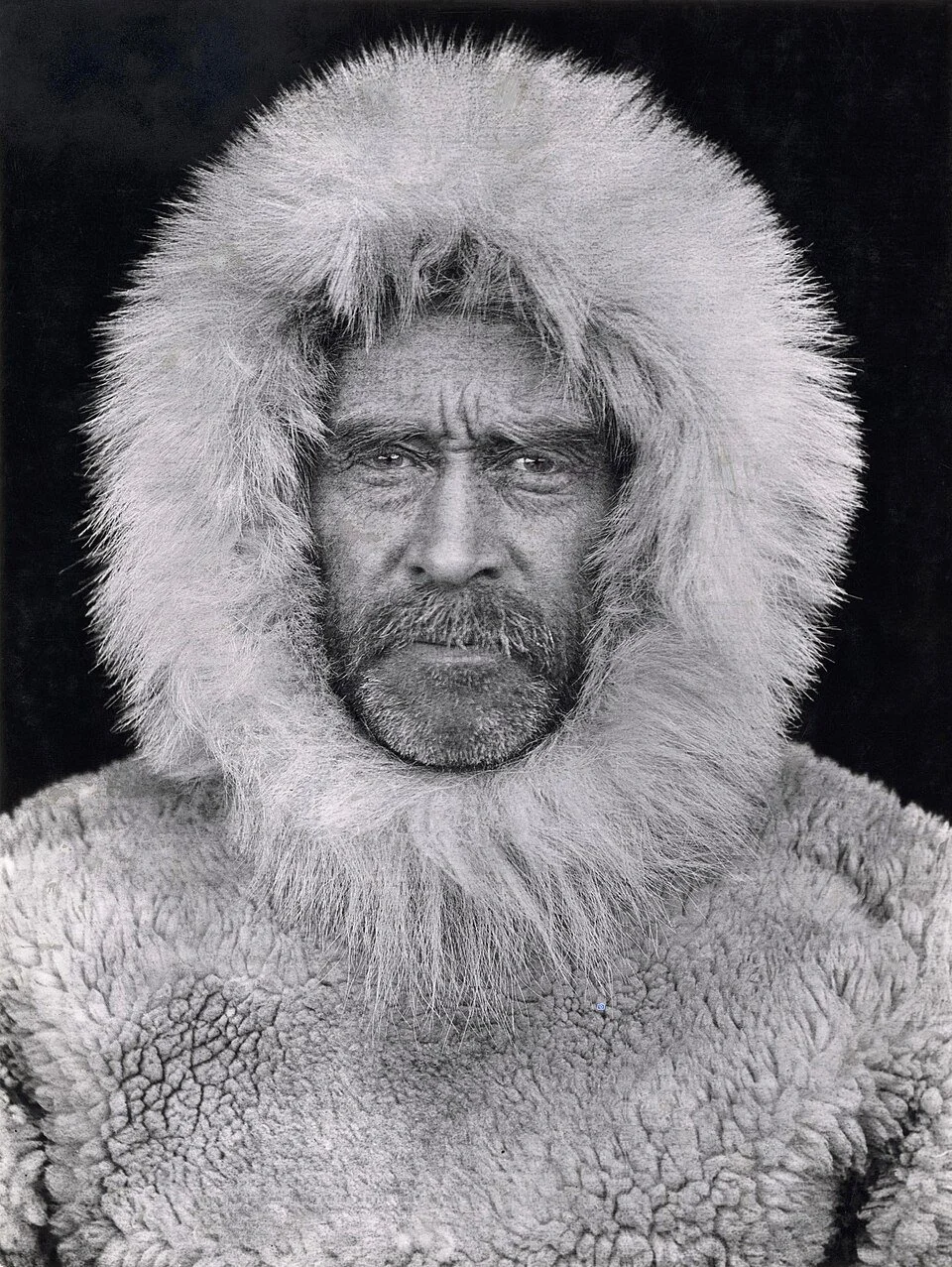

The Peary Land Controversy: An Attempted Claim by Exploration

Robert Peary in full Arctic gear

TLDR & Spoiler: Why the Claim Failed

The Peary Land claim ultimately collapsed for several reasons:

Later expeditions proved Peary Land was not an island, but part of Greenland’s main landmass

Denmark had longstanding colonial and administrative control over Greenland

The U.S. government declined to pursue Peary’s claim diplomatically

International norms increasingly rejected explorer-based territorial claim

By the early 20th century, the matter was effectively settled in Denmark’s favor.Shortly after the question of Denmark’s sovereignty over Greenland was settled, American interest through exploration and attempted territorial claims, seemingly almost immediately afterwards. Named after Robert Peary, which is also the subject of our “Five Famous Explorers” blog post, Pearyland was a proposed island in the north of Greenland. Being an island, in theory, would make it a separate landmass from the Greenlandic mainland. Peary believed that Peary Land existed because of observations he had made during his expeditions, including sightings of distant land and reports of Inuit communities living on the island.

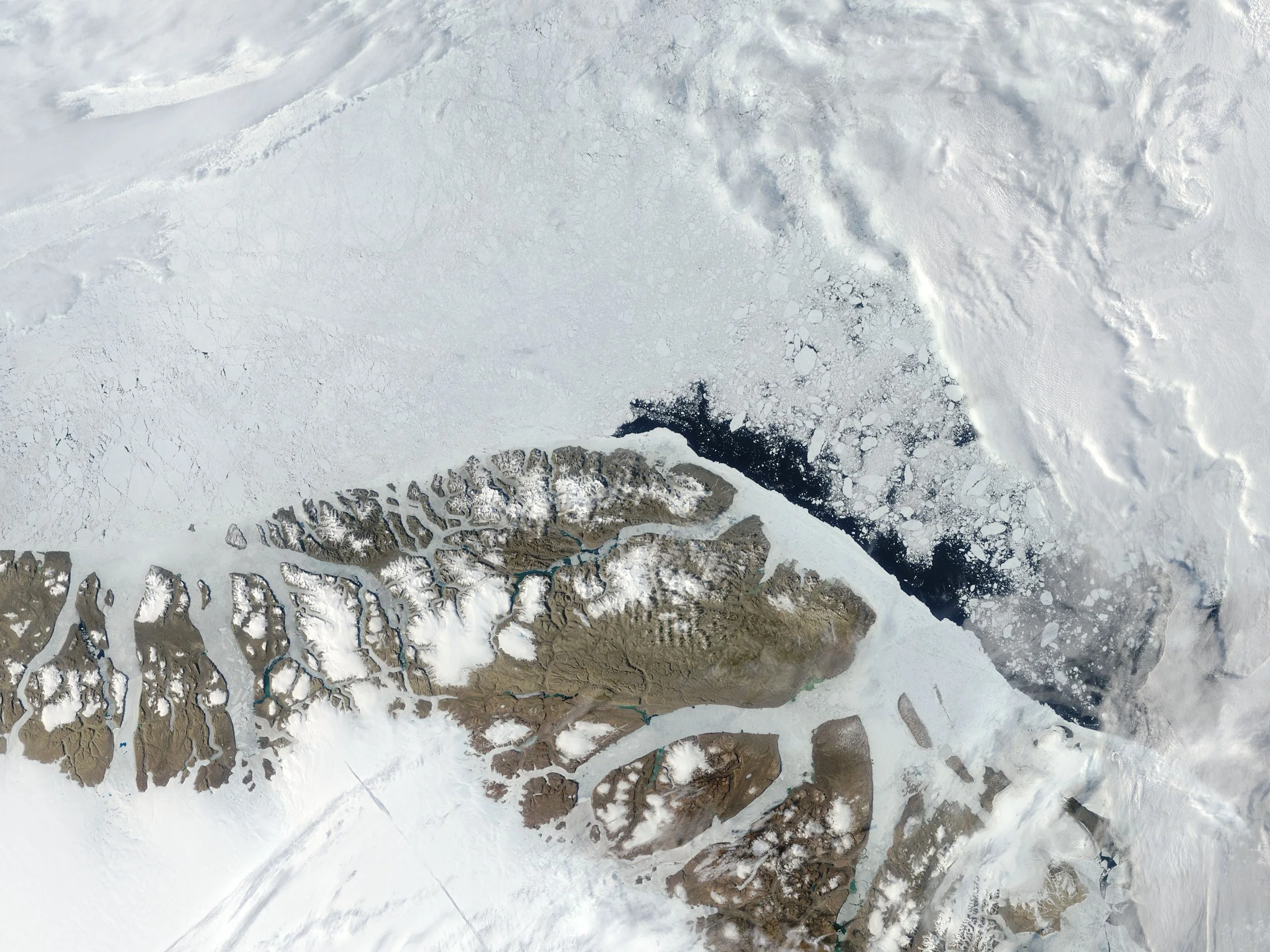

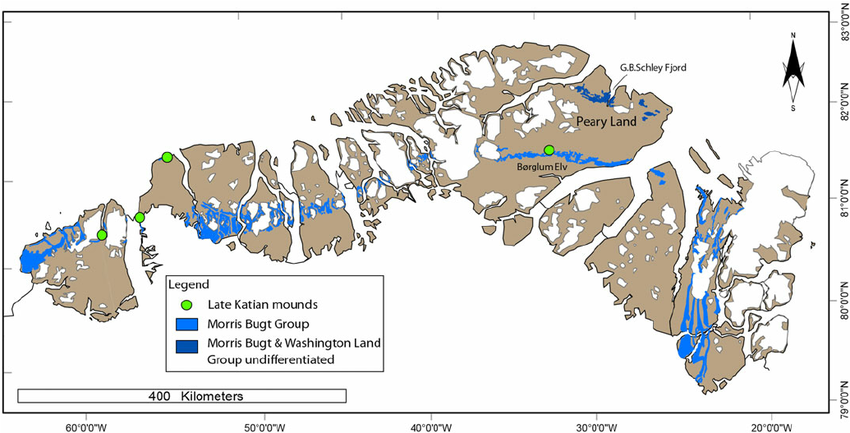

However, it's now believed that these sightings were likely due to mirages or other optical illusions, and that Peary Land never actually existed. There was also a proposed “Peary Channel” that cleaved Peary Land from the mainland. The three figures below show Peary Land as it was proposed, and then as it actually is on a detailed topographical map.

Pearyland in the contect of the Arctic

Pearyland, isolated

Pearyland, close-up satellite

Pearyland, topographical

The significance of the existence of Peary Land was not merely academic. If Peary had discovered a new island, this would have lent credence to a potential second American territorial claim in the Arctic.

The Danish launched a counter expedition to prove that Peary Land was false. Indeed, it was the findings of Ejnar Michelsen’s ‘Alabama’ (ironically titled in our opinion) expedition in the years that followed that made it possible to categorically dismiss the existence of Peary and re-affirms Denmark's territorial claim to the entirety of Greenland. Ejnar Michelsen’s counter expedition successfully proved that Pearyland was not, in fact, and island. The United Statsu would not have, buy or acquire Pearyland, because it is part of Greenland, and therefore belongs to Denmark. Ejnar Mikkelsen, whose bust stands in the town of Ittoqqormitt, a town he helped to found, is frequently visited on our Greenland Expeditions. Ejnar Mikkelsens counter expedition is dramatically captured in his volume “Two Against the Ice” and then dramatised in a movie with the same title.

Importantly, Peary’s claim was not authorized by the U.S. government, nor was it followed by any formal annexation. However, it carried political weight. His actions reflected a broader American mindset of the era, when explorers often acted as informal agents of national expansion, particularly in polar regions.

Confusingly, the area retains its name, Pearyand, but it is instead a peninsula of the northernmost part from the mainland.

Why the Peary Land Controversy STILL Matters

Although unsuccessful, the Peary Land episode is significant because it represents the only time an American citizen explicitly attempted to claim part of Greenland for the United States.

It also illustrates a recurring pattern:

Moody skies and brilliant icebergs in Scoresby Sound

The U.S. asserting influence through science, exploration, or security

Denmark reaffirming sovereignty through law and diplomacy

Greenland itself having little voice in decisions made about its territory

Today, Peary Land lies within Northeast Greenland National Park, the largest national park in the world, which The Great Expedition Company visits annually on our Svalbard to Greenland expedition.

World War II: A Strategic Turning Point (1941-1945)

The United States’ most significant involvement with Greenland began during World War II and continues to this day. When Nazi Germany occupied Denmark in 1940, Greenland was suddenly vulnerable. Greenland was suddenly cut off from its governing authority and vulnerable to foreign control. To prevent German forces from gaining a foothold, the U.S. moved to defend the island.

Externsteine shortly after its capture by the Eastwind

In 1941, with the consent of Danish representatives in exile, U.S. forces assumed responsibility for Greenland’s defense. American troops constructed airfields, weather stations, and military infrastructure across the island. While Greenland technically remained Danish territory, the United States exercised de facto military control throughout the war. This marked the first sustained American presence on the island and firmly embedded Greenland into U.S. defense planning.

1946: The Truman Purchase Offer

The most explicit and formal attempt by the United States to acquire Greenland occurred in 1946, when the administration of President Harry S. Truman offered to purchase the island outright from Denmark. Coming just months after the end of World War II, the proposal reflected a rapidly changing global order in which the Arctic had become a central front in emerging Cold War strategy. American policymakers now viewed Greenland not as a remote possession, but as a critical military asset whose location made it indispensable to U.S. national security.

By National Archives and Records Administration. Office of Presidential Libraries. Harry S. Truman Library. - NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION (NARA) - CATALOG: AUDIOVISUAL MATERIAL (ID. 7865583)., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79198241

Why? Well, as the Cold War emerged, Greenland’s location made it ideal for:

Early warning radar systems

Air bases between North America and Europe

Monitoring Soviet activity in the Arctic

The United States offered $100 million in gold to buy Greenland, a sum intended to underscore the seriousness of the proposal rather than serve as a precise valuation. The logic behind the offer was straightforward and strategic. Greenland’s position between North America and Europe made it ideal for long-range bomber routes, early warning radar systems, and the monitoring of Soviet activity across the Arctic. With tensions rising between Washington and Moscow, American defense planners feared that any gap in Arctic coverage could expose the continental United States to surprise attack. From this perspective, acquiring Greenland was seen as a preventative measure.

Danish officials rejected Truman’s offer, insisting that Greenland was not for sale and reaffirming their sovereignty over the island. At the same time, Denmark recognised the strategic realities of the postwar world and the limits of its own ability to defend such a vast Arctic territory alone.

1951: The U.S.–Denmark Greenland Defense Agreement (Bases Without Buying)

Fast forward a few years to 1951, five to be exact. Where 1946 was about trying to buy Greenland, 1951 was about ensuring the United States could operate in Greenland indefinitely without purchasing it. On April 27, 1951, the United States and Denmark signed the agreement commonly referred to as the Greenland Defense Agreement, concluded within the framework of the North Atlantic Treaty era. Rather than transferring sovereignty, the agreement established the legal basis for U.S. defense activity in Greenland: it allowed the United States to maintain and operate installations and, crucially, to establish additional facilities and “defense areas” in cooperation with Danish authorities, while explicitly preserving Danish sovereignty.

Extract form the Defence agreement

This agreement is the real foundation of Cold War Greenland as we have come to know it. It formalized what had begun during WWII (when the U.S. took on Greenland’s defense after Denmark was occupied) and converted that wartime arrangement into a stable, treaty-based relationship. One of its most consequential outcomes was enabling large-scale U.S. bases in northwest Greenland, most famously Thule Air Base (now associated with the modern U.S. installation at Pituffik) which became deeply tied to early warning systems and Arctic surveillance during the Cold War. 1951 wasn’t a “purchase” attempt at all. It was a way of achieving many of the same strategic ends: access, infrastructure, reach, and presence through alliance law and defence agreements rather than annexation.

Decline in United States Military presence in Greenland

The status Quo for the Greenland Treaty held for decades: America was allowed to have its bases and its troops and this arrangement worked well. In fact, it was The United Status that decided to gradually reduce the number of troops at the bases in Greenland, and the number of bases. Under the Greenland Defence Agreement, Washington built and staffed dozens of installations that were pivotal to North Atlantic defense planning. By the mid-1950s and into the 1960s, at the peak of Cold War deployment, as many as 10,000 U.S. military personnel and support staff were stationed on the island, with large garrisons at major locations like Thule Air Base and other early-warning radar and logistics sites.

Map of Present and former US military bases in Greenland.

This massive presence was tied to broad Cold War strategy, including the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line radar network and NORAD’s northern defense posture. Some Greenlandic installations, like Camp Century, even embodied experimental Cold War programs such as Project Iceworm, though they were closed by the late 1960s. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, advances in surveillance technology, changes in strategic doctrine, and the reduced emphasis on large ground forces in fixed Arctic locations began to diminish the need for such a heavy footprint.

By the early 21st century, most of the former facilities that once housed tens of thousands of U.S. troops had been dismantled or repurposed, leaving only one major American outpost. Pituffik Space Base, formerly Thule Air Base, became the centerpiece of what remained of U.S. operations on the island. Under agreements with Denmark, the base continued to support missile warning, space surveillance, and early-warning radar functions essential to both U.S. and NATO defense systems. As of 2025–2026, the total number of U.S. military personnel permanently stationed in Greenland had fallen to roughly 150 service members, a tiny fraction of the peak Cold War force.

2019: Trump Revives the Idea of America Buying Greenland

In 2019, President Donald Trump reignited global attention by openly expressing interest in buying Greenland from Denmark., although this was not treated entirely seriously in the beginning. The proposal surprised both allies and observers, but it echoed earlier American attempts to acquire the island.

The motivation behind the proposal was rooted in modern Arctic geopolitics. The Trump Administration had identified Greenland as strategically important due to its location, emerging Arctic shipping routes, and growing competition with Russia and China. From Washington’s perspective, Greenland’s value lay in military access, surveillance, and long-term strategic positioning, not unlike earlier Cold War calculations.

The situation in Greenland is looking a but icy

The response from Greenland and Denmark was immediate and decisive. Greenlandic leaders stated that Greenland was not for sale, emphasizing self-government and political autonomy, while Danish officials reaffirmed sovereignty. After Denmark publicly dismissed the idea, President Trump canceled a planned state visit, briefly straining diplomatic relations. Although no formal negotiations ever occurred, the episode demonstrated that American interest in Greenland did not end with the Cold War . It simply reappeared in a more visible and unconventional form.

“One way or the other, we’re going to get Greenland” - The 2025–2026 Greenland Crisis: Renewed U.S. Pressure and International Response

The most recent and serious chapter in the long history of American interest in Greenland began throughout 2025 but seemingly came to a head in December, when U.S. President Donald Trump escalated his efforts to assert American control or influence over the strategically important Arctic island. Trump took the subject further in 2025 by publicly declaring that “we have to have it” for national security and appointing Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry as a special envoy with the informal mission of integrating Greenland with the United States: a move Denmark called “completely unacceptable” and damaging to bilateral trust.

Vice President JD Vance at Pituffik Space Base in Greenland, 28 March 2025. By U.S. Space Force photo by Staff Sgt. Jaime Sanchez - This image was released by the United States Space Force with the ID 250328-X-IL270-1325

Trump argued in late 2025 that Greenland was “essential” to U.S. national security and suggested the United States might pursue control of the island “one way or another,” including by force: a shift that alarmed allies and neighbors alike. In response, the Greenlandic and Danish governments have repeatedly rejected any U.S. takeover, with Greenland’s prime minister stressing that decisions about the island’s future must be made by Greenlanders and Danes, and Denmark’s leaders defending Greenland’s sovereignty as a non-negotiable part of the Kingdom of Denmark.

The dispute has triggered a rare and significant military and diplomatic reaction from U.S. allies, somethign that would have been hitherto unthinkable: European NATO members, led by Denmark, have begun reinforcing the island’s defense posture through joint exercises and rotational deployments under initiatives such as Operation Arctic Endurance, which brings forces from countries including France, Germany, Sweden, and Norway to Greenland for reconnaissance, infrastructure protection, and Arctic training operations. Denmark has also expanded its own military presence around Greenland in coordination with NATO allies, deploying aircraft, vessels, and soldiers in 2026 to demonstrate collective commitment to Arctic security and to counterbalance unilateral U.S. pressure. Meanwhile, Russia has criticized NATO’s Arctic buildup as unnecessary hysteria, underscoring how the Greenland crisis has reverberated far beyond the North Atlantic and into broader East-West tensions.

Unlike earlier episodes in U.S.–Greenland relations characterised by purchase offers or Cold War basing agreements, the 2025–2026 crisis reflects a more urgent and contested phase, appearing to signal real intent to take action and not merely hyperbolic. It involves not just Washington and Copenhagen, but the full NATO alliance and other global actors whose troop deployments and strategic postures signal that Greenland’s future is now a central element of contemporary geopolitics.

Icebergs top down

Recap: Why the U.S. Has Always Wanted Greenland

Across more than 150 years, American interest in Greenland has been driven by:

Geography: Control of Arctic air and sea routes

Military strategy: Missile defense and early warning systems

Natural resources: Rare earth minerals, oil, and gas

Climate change: Emerging Arctic shipping lanes

While ownership never materialized, Greenland has remained a critical part of U.S. strategic thinking.

For more than a century, the United States has repeatedly tried to buy, acquire, or otherwise take control of Greenlandwhenever global conditions made the Arctic strategically important. Early interest emerged alongside 19th-century American expansion, followed by informal claims through exploration and later by diplomatic trade-offs that prioritized other regions over Greenland.

More recent episodes, including the Trump administration’s proposals and the renewed international tensions beginning in late 2025, show that Greenland’s importance has not faded. Instead, it has shifted from a quiet strategic asset to an openly contested one, drawing in allies and provoking international responses. The pattern is consistent: Greenland’s geography ensures that whenever global power dynamics change, the United States returns to the same conclusion : that Greenland matters and Greenland is important: the subject of our last blog post

Coming into land at Constable Point Airport (CNP)

It Comes Down to You: Greenland Beyond the Headlines

Much of Greenland’s modern history has been shaped by how others have viewed it: as territory to be acquired, a position to be defended, or a problem to be solved on a map. Yet these narratives, repeated over generations, rarely capture what Greenland is like when encountered on its own terms. Beyond strategy and sovereignty lies a place defined by silence, scale, and movement: ice drifting through fjords, weather shaping every decision, and coastlines that reward patience rather than control.

Our sailing expeditions are an invitation to experience that Greenland directly. Moving slowly by sea offers a perspective that no policy paper or headline can provide: one grounded in observation, humility, and presence. For those who have followed Greenland’s history through words, sailing its waters is a way to step beyond them, and to form your own understanding of a place that has long been discussed, but rarely known.

If you’re curious to explore Greenland not as an idea, but as an ethereal and other-worldly landscape, we’d be glad to welcome you aboard. All expedition participation is on the condition of a phone call/interview with the Expedition Leader.

Our Greenland Expeditions for 2026

Beluga Whales, Svalbard

Sunset over Schooner

Towering Icebergs, Greenland

Majestic Mountains, Greenland